Two Souls of Scottish Independence

An exclusive extract from the conclusion to Scotland after Britain, a new book from Verso by Conter contributors James Foley and Ben Wray.

You can buy the direct from Verso’s website at a 30% discount and with a free ebook - buy here.

Exploring the weaknesses in Scottish nationalism need not mean abandoning an unapologetically expansive idea of national independence. Indeed, knowledge of the former is the necessary foundation of the latter. Contradictions, we argue, inevitably follow from the tension of being both a social movement and a party of power. That is why we speak of independence having ‘two souls’. This is not the same as saying that Scotland’s national psyche is uniquely contorted, or even ‘schizophrenic’, as the country’s popular sociology has sometimes implied. Scotland’s problems of cultural polarisation and electoral fragmentation are real enough, but hardly exceptional. Indeed, far from seeing the national question as an irrational expression of Scottish particularity, it is rather what unites Scotland to other European societies, all of them riven with social conflicts which, in the absence of institutional channels, erupt in unexpected bursts of chaotic political energy. Davidson was thus fond of quoting the French theorist Daniel Bensaïd: ‘If one of the outlets is blocked with particular care, then the contagion will find another, sometimes the most unexpected.’

In seeking to reclaim a certain idea of independence, the ‘two souls’ concept is a conscious reference to the American Marxist theorist Hal Draper. His ideas were drawn from very different historical circumstances. Nonetheless, there is a real analogy with his defence of ‘socialism from below’ against the encroachment of ‘socialism from above’, represented not just by Stalinism but by European social democracy, the labour movement bureaucracy, and even many forms of anarchism. Draper wrote:

‘What unites the many different forms of Socialism-from-Above is the conception that socialism (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) must be handed down to the grateful masses in one form or another, by a ruling elite which is not subject to their control in fact. The heart of Socialism-from-Below is its view that socialism can be realised only through the self-emancipation of activised masses in motion, reaching out for freedom with their own hands, mobilised ‘from below’ in a struggle to take charge of their own destiny, as actors (not merely subjects) on the stage of history.’

Of course, the Scottish independence movement is not socialist as such (although it does largely encompass that tradition); but Draper observes that the dualism is ‘not peculiar to socialism’ but a feature of all class-based societies. ‘The yearning for emancipation-from-above is the all-pervading principle through centuries of class society and political oppression’, he observes. ‘It is the permanent promise held out by every ruling power to keep the people looking upward for protection, instead of to themselves for liberation from the need for protection…Instead of the bold way of mass action from below, it is always safer and more prudent to find the “good” ruler who will Do the People Good.’ Sturgeonism has represented a post-neoliberal rule of ‘doing good from above’. Its popularity, including with much of the actually existing Scottish left, is standing testament to the absence of an agenda for independence from below.

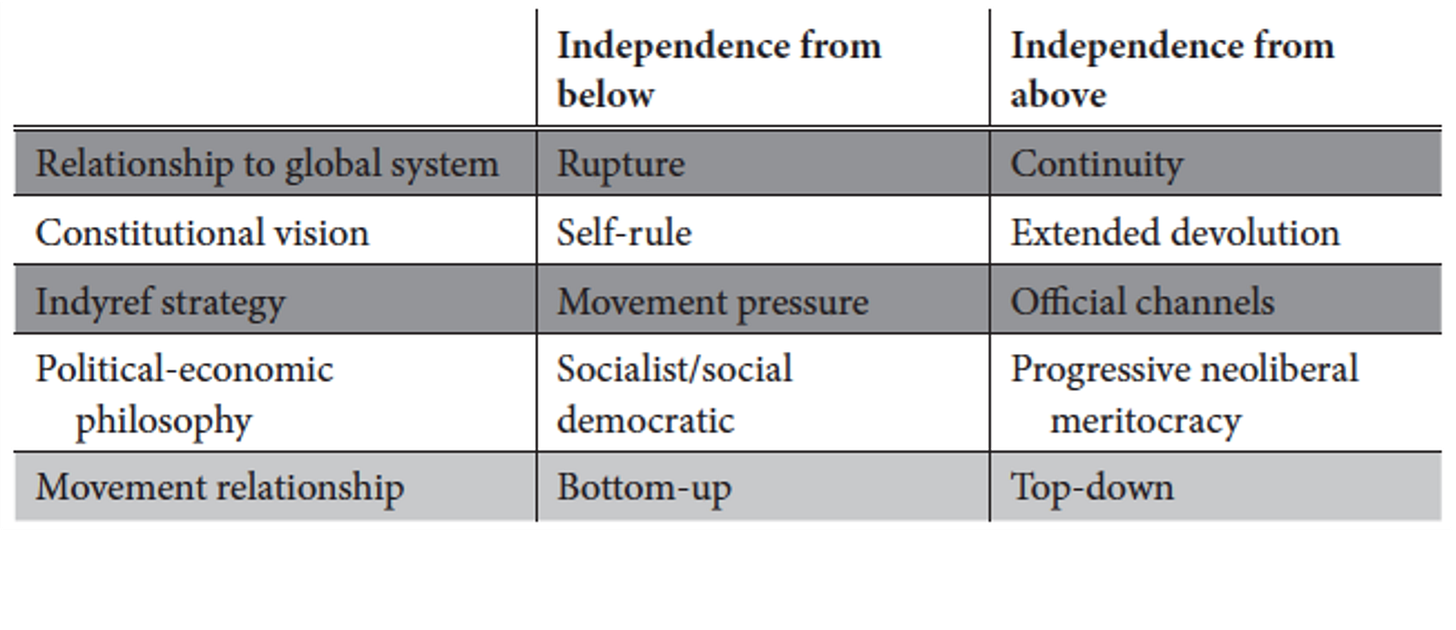

There are thus strong affinities between Draper’s distinction and the strategic dilemmas of the independence movement, as we illustrate in the table below.

In applying this to the real world, the same caution must be exercised as with any abstract dichotomy drawn from political science. These concepts are ideal-types, and are not neatly separated within the independence movement. The spirit animating Scotland’s mass movement is not always one thing or the other, but rather overwhelmingly pragmatic. Nonetheless, while the two souls may be difficult to separate in real cases, and may even be at war within one individual, they do represent distinct poles of attraction – rival meanings, competing class interests and conflicting relationships to state power.

Since 2014, the balance between these competing forces has swung back and forth. However, for all the extraordinary vigour of the street protests, the intellectual momentum has been with independence from above. This factor deserves deeper consideration than it often receives from liberal critics, who often complain of the wayward thinking and absence of serious intellectual calibre within the idealistic movement, relative to the ‘credibility’ of SNP figureheads like Sturgeon and Wilson. In turn, this narrative forms the basis of stock contrasts between ‘utopianism’ and ‘pragmatism’. Certainly, independence from above has a programme – the Sustainable Growth Commission – while the other pole, for all the efforts of grassroots groups like Common Weal, remains fuzzy and inconclusive.

Nonetheless, we would caution that the utopianism-versus-pragmatism framing risks eliding crucial nuances. Firstly, there is a risk of missing the strongly utopian character to the SNP leadership’s centrist programme. Wilson draws on the energy of nostalgia for a return for the booming, liberal nineties economy, but his vision of open markets is riddled with inconsistencies and unresolved conflicts: for example, between sterlingisation and membership of the EU Single Market. His programme has been rendered incoherent precisely because the historical conditions for neoliberal globalisation have passed. While it may be possible to persist with the old solutions, it would almost certainly come at the cost of substantive economic, environmental and social progress. In other words, what passes for a mainstream vision of independence would depend on a mixture of dogmatism and utopian nostalgia: it is ‘pragmatic’ only insofar as it is easier to sell to Scotland’s boardrooms.

Secondly, there is arguably an exaggerated pragmatic streak to much of the street movement. Indeed, it is the movement’s sheer pragmatism – anything to get over the line to independence – that leads it to flail between implacable trust in the leadership and bursts of rage when Sturgeon flouts the movement’s desires because she dares not disturb the settled devolved order that reproduces the SNP’s position in power. Dogmatic ‘pragmatism’ ensures that the street movement, just as much as Sturgeon, fails to confront the big challenges that all states face after the 2008 crisis: climate breakdown and the coronavirus pandemic.

Throughout the book, we have stressed the weaknesses of independence from above – its mixture of utopianism (‘normality’ will be restored simply by joining the ‘mainstream of Europe’) and cynicism (manipulating the national divide to secure constant re-election while minimising scrutiny of state power). We recognise the incoherence at the pole of independence from below. However, we do not make these criticisms from the standpoint of bad faith and passivity. Our goal throughout the book has been to face with honesty the challenges facing Scotland as a European society undergoing extreme restructuring and economic failure. In this spirit, we will attempt to outline the concepts that could define a coherent movement. This is not the same as a comprehensive programme for socialism, if only because the radical left is some way from winning the consent of the majority for a real challenge to capitalism. However, we believe that reimagining the state around the themes of popular sovereignty may remove some of the barriers to addressing climate breakdown, extreme inequality and corporate oligarchy. Given these challenges, the left’s goal should be to maximise the space for democratic authority over economic decision-making, and to minimise constitutional limits to the latter.

Exclusives on Patreon

ConterIdeology: Neo-Blairite Brain Fog

This week, we're talking Labour. Why is the party sacking people for attending picket lines? Is Starmer more right-wing than Blair? Has the Forde Report finally demonstrated, beyond doubt, that a right-winger faction weaponised anti-Semitism allegations to bring down Corbyn? Also, the less heralded Blairites of the Scottish Government have been accused of reintroducing one of Scotland's most regressive measures by the backdoor. We talk about the Poll Tax legacy and the role of poindings and warrant sales under early devolution.

Zombie Thatcherism and the Decline of the Tory Party

The contest for the next leader of the Tory party and our next PM is as stale as it is furious. We speak to Phil Burton-Cartledge, author of Falling Down: The Conservative Party and Decline of Tory Britain, about what we can learn from the contest about the past and future of the leading party of British capitalism. And ask, is the party in decline?

A History of the Orange Order in Scotland and Ireland

Simultaneously dreary and whacky, Orange marches are an annual reminder of the contradictions in our various nationalist traditions. David talks to historian Chris Bambery, author of a forthcoming book on the Orange Order in Scotland and Ireland.

Free on Conter

Why the Telecoms Strikes Matter

Strikes in the private sector, in industries with a sparse record of industrial action, imply a re-politicisation of work. But this will be a long process, argue Lewis Akers and David Jamieson. And it’s already under attack from employers and governments.

Inching Towards War With China

Jenny Clegg looks at the west’s steady escalation in east Asia, and the mounting threat of war with China.

“Strikes Will Need to be Generalised”: united Fightback on CWU Pickets

We spoke to workers on CWU picket lines in Glasgow during an historic telecoms strikes.